Race in America: The Southern Strategy

How Republicans went from whispering racism to saying the quiet part out loud.

This is the first of a two-part series on American race relations in the latter half of the 20th century. Much of our current understanding of Black History ends at the Civil Rights Movement. Its imperative to reflect on race in American history after that moment to understand how we got to where we are today. This piece focuses on White Americans who inflamed racial anxieties to attain political power. This companion piece focuses on the same time frame from the perspective of Black Americans and the ways in which they organized to combat oppression.

Topline Takeaways

The Southern Strategy is a “top-down” narrative of the political realignment experienced in the American South during the latter half of the 20th century.

The Republican Party capitalized on white voters’ anxieties surrounding the Civil Rights Movement, leading many southern states to support Republican presidential candidates for the first time in nearly a century.

Richard Nixon contributed to the Southern Strategy by perfecting the “dog whistle:” pushing policies with racially discriminatory effects while purposefully obfuscating his racist intentions to maintain support.

Ronald Reagan built on Nixon’s strategy by introducing the “welfare queen:” an image that encouraged White voters to demonize benefit-seeking Black voters without ever explicitly mentioning race.

Barack Obama’s tenure as president created a false sense of racial progress that was later abused by President Trump. Under Trump, many Republicans pushed “race-blind” policies that entrenched systemic racism instead of addressing it.

The Southern Strategy persists today as a way to prevent Americans from meaningfully confronting the remnants of white supremacy.

The “Solid South” (1867-1964)

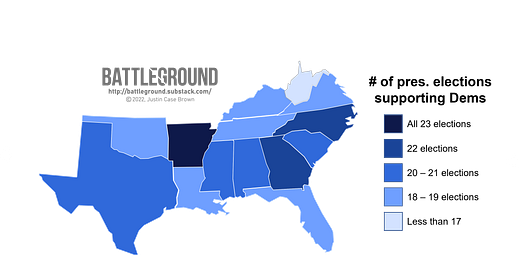

From the end of Reconstruction in the late 1800s until the presidential election of 1968, most former states of the Confederacy (and a couple border states) were dubbed the “Solid South.” It reflected these states’ unwavering commitment to the Democratic Party, spurred by white Democrats who held a laser-focus on preserving white supremacy in the face of racial progress. The Democratic party of the early 1900s more closely resembled the Republican party of today: state legislators across the South passed a bevy of laws that made it more difficult for Black people to vote. This included procedures like poll taxes, literacy tests and onerous residency requirements. These restrictive voting laws helped keep white legislators in power as much of the Black electorate was prevented from casting a ballot in elections.

Barry Goldwater: The Trump Prototype

Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign shares many similarities with Trump’s path to the nomination in the 2016 presidential election. Barry Goldwater, an heir to his family’s department store chain, emerged as a frontrunner candidate in the Republican Party due to his rough-edged, hard-line rhetoric. His campaign was supported by Southerners and Midwesterners who felt sidelined by the more moderate, metropolitan wing of the party (symbolized by primary challenger Nelson Rockefeller).

What propelled Goldwater to the nomination was his relatively extreme political positions in the face of a moderate Republican party (primary challengers cast him as an “extremist” and “ignorant”). His political ideals were deliberately formed to court white voters in the South, clearly signaled by his opposition to emerging civil rights legislation. While serving in the Senate in 1964, Goldwater voted against the Civil Rights Act, claiming that the law amounted to federal overreach and that states should be able to control their own laws without federal intervention. Many within the party picked up on the racist undertones of the statement and voters did too. While Goldwater lost in a landslide election to Lyndon B. Johnson, Republican political observers took note on exactly how Goldwater cracked the Solid South.

The “Dog Whistle”

“[President Nixon] emphasized that you have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the Blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to.” -a diary entry from H.R. Haldeman, former White House Chief of Staff

Richard Nixon watched Barry Goldwater’s campaign closely. While he saw the benefits from capitalizing on the racial anxiety of Southern white voters, he also saw the perils of saying the quiet part out loud. In his attempt to court the Democratic-leaning Southern states, Goldwater clearly alienated the rest of the country. In his 1968 presidential campaign, Nixon mirrored Goldwater’s strategy: using terms such as ‘state’s rights’ and ‘law and order’ to slyly signal his opposition to African American progress. The key difference for Nixon was the presence of an even more radical primary candidate who was yelling the quiet part through a megaphone.

The 1968 election also saw the candidacy of George Wallace, a nakedly racist third-party candidate who stole several states in the Deep South away from both Nixon and the Democratic party. The presence of a clearly extremist candidate helped Nixon cast himself as a moderate: his campaign operatives were able to downplay his more covertly racist rhetoric by instead focusing on the more brash and appalling style of his opponent. By the time Nixon ran for re-election in 1972, he won every state except Massachusetts, proving that “dog-whistle” tactics provided an avenue for Republican success across the country.

The ‘Welfare Queen’

After a decade of dog-whistles, racial justice advocates were beginning to call out Republicans’ insidious rhetoric on race. That forced the party to innovate:

“You start out in 1954 by saying, "Nigger, nigger, nigger." By 1968 you can't say "nigger"—that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states' rights and all that stuff. You're getting so abstract now [that] you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I'm not saying that. But I'm saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me—because obviously sitting around saying, "We want to cut this," is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than "Nigger, nigger."

-Republican strategist Lee Atwater in 1981

Ronald Reagan waged a war against the “welfare state” since his stint as California’s governor in the early 1970s. Then in 1976, he started telling the story of a woman from Chicago who used fake names and addresses to collect illegal welfare payments. While he never racialized her or even used her name, this one woman’s story was used to generate clear racial animus against African Americans. The face of welfare recipients in the media at the time was undeniably Black, therefore Reagan was able to capitalize on voters’ internal biases without ever explicitly mentioning race. The tactic proved to be a little too covert for voters as Reagan failed to capture the nomination in his first primary campaign. Enter the “welfare queen.”

It wasn’t until Reagan’s winning campaign in 1980 that he uttered the phrase “welfare queen” on the campaign trail and the imagery directly influenced his policies once in office. In his inaugural address, he lamented the amount of fraud in government programs and his administration oversaw $25 billion in cuts to welfare benefits.

By the end of the 1980s, public opinion on racial progress was mixed. Polling showed progress on integration amidst widespread intolerance. The percentage of white Americans living in all-white neighborhoods dropped from nearly half (47%) to almost a third. Yet at the same time, more than half of White parents living in mixed neighborhoods cited an unwillingness to let their children play with children of other races. More than half of White Americans continued to believe that issues faced by Black people “were caused by Blacks themselves.” Meanwhile, a majority of African Americans agreed that they saw more racial progress in the 1970s than in the 1980s. (No wonder Reagan’s approval rating averaged about 25% among Black voters.)

“Take Trump Seriously, Not Literally”

The election (and re-election) of the country’s first Black president contributed to a false sense of progress among the American public. For many, the existence of a Black president was in itself a sign that the country had finally overcome its racist history. Democratic moderates lauded the emergence of a new “post-racial society.” The Republican Party acknowledged how it was being held back by an inability to invite a more diverse coalition of voters. While this was intended to be a launching point for continued social change, it was used to bolster arguments on the far-right that racism had gone extinct, meaning legislation protecting racial justice was largely unnecessary.

“First, according to the arguments, a nation that has the ability to elect a Black president is completely free of racism. Second, attempts to continue the remedies enacted after the civil rights movement will only result in more racial discord, demagoguery, and racism against White Americans. Third, these tactics are used side-by-side with the veiled racism and coded language of the original Southern Strategy.”

Actions across all levels of government in the last decade underscore the precarious state of racial justice progress:

In 2013, the Supreme Court invalidated Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, allowing many southern states to change their voting laws without federal government oversight for the first time in 50 years.

In 2017, Donald Trump penned an executive order explicitly targeting foreign nationals from Muslim countries, banning them from entry to the United States.

In 2021, 19 states enacted laws that added new restrictions to voting, following an election with the highest voter turnout since 1900.

In 2022, the Supreme Court allowed several alleged racial gerrymanders to remain in place for the midterm elections.

Continued evolution of the Southern Strategy is what allowed this slow rollback of progress to take place. In 2016 we were told to “take Donald Trump seriously, not literally.” To decipher his ramblings, we were forced to wade through the bigly covfefe of it all to hear the messages his supporters received. From states’ rights to “shithole” countries, Donald Trump trafficked in traditional racist dog whistles and even created a few new ones of his own. When challenged, conservatives point to his Black predecessor and lean on the post-racial myth that many moderates still believe in today.

This convinces some to carve a path forward that avoids confronting racism directly. It inspires them to lean into supposed “race-blind” policies that fail to address racism and only encourage ignorance to growing societal problems. Most importantly these types of arguments sway moderate Democrats, allowing Republicans just-barely-enough power to stymie any further progress. It also lays bare as to why Critical Race Theory has been used as a bit of a “boogeyman” by the party on its own voters.

CRT: Countering The Southern Strategy

Critical Race Theory forces us to reckon with history and exposes the rhetorical games bad actors listed above have played for decades. Without this hisotry, “race-blind” policies sound great. ‘How could this possibly lead to racism if they’re trying their hardest to ignore race?’ Retracing our steps through history proves how Americans readily avoid confronting racism directly. Politicians and pundits take advantage of this squeamishness: transforming fear and ignorance into harm and hatred.

The Southern Strategy plainly seeks to answer the question: “How can White Americans most benefit from stoking racial anxiety?” Throughout the late 20th century, White Americans benefitted most by doing so quietly; hiding their klan robes and cleaning up their speech. But when we pull states’ rights, welfare queens and ‘shithole’ countries out of their contextual vacuums and place them squarely beside our country’s historical patterns of racism and power; it lays bare the ways powerful people routinely take advantage of America’s chronic racial denialism.

The strategy allows politicians to sidestep race issues by making oppressed people appear as though they’re creating their own problems. It even affords voters plausible deniability when dubious political intentions lead to clearly harmful impacts. Most importantly: the Southern Strategy gives Americans an ‘out’ from meaningfully confronting the scraps of white supremacy left on our plate. Because most of us simply won’t admit to ourselves that we’re willing to tolerate racism as long as it’s served with a wink and a smile.

Leftover Links

The Southern Strategy is continuing to evolve into its next phase: blaming immigrants and racialized minorities for the COVID-19 pandemic. See how tactics recently used by the far-right fit within a larger historical context.

Learn how the Republican party turned Critical Race Theory into its own dog-whistle.