The Micropolitan Party: Republicans Embrace a Small-City Strategy

The Democratic party's urban approach only focuses on cities of a certain size. Republicans are swooping in to pickup the smaller cities and towns that are often ignored.

What is a “Micropolitan Area?”

The Office of Management and Budget created this designation in 2003 and defines a micropolitan area as “a labor market… in the United States centered on an urban cluster (urban area) with a population of at least 10,000 but fewer than 50,000 people.”

The true size of a micropolitan area is larger than its urban cluster: some of the largest “micros” in the nation comprise as many as 250,000 residents. That may sound large, but we’re talking about cities like Appleton, Wisconsin and Tupelo, Mississippi. These are cities that have almost no national profile and are likely unknown to out-of-state residents. I applied this definition to my US House district classification system: if a House district held a micropolitan area that was less than 250k, I labeled it a “rural micropolitan district.” (Rural Micro for short.) As a reminder: the 2020 census requires each House district to hold roughly 760,000 residents for equal representation. This means that more than 2/3rds of voters in these “rural micro” districts live outside of that micropolitan area in distinctly rural conditions.

Micropolitan districts are dominated by Republicans.

In total, I counted roughly 90 rural micropolitan House districts across the country and 38 states have at least one “rural micro” district. Of those 90, a whopping 75 districts (83%) voted in favor of Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election and 69 districts (76%) are represented by Republican House incumbents. Not only do most of these districts lean toward Republicans, many of them lean heavily toward the party. The average 2020 pres. vote margin across all “rural micro” districts was a whopping 20 points in favor of Trump and 13 districts supported Trump by a margin of 40 points or more. The reasons why Republicans perform so well in these districts are pretty straightforward when you start paying attention to the demographic qualities of these places.

Micropolitan districts are heavily White.

When looking at the nonwhite populations of these districts, only 8 rural micropolitan districts across the country are majority nonwhite and nearly half are more than 80% White. This helps illustrate why the far-right wing of the Republican party is embracing clearly racist, white supremacist rhetoric. The districts where they’re seeing the most success are districts where White residents not only makeup a hefty majority, they’ve dominated positions of power for generations.

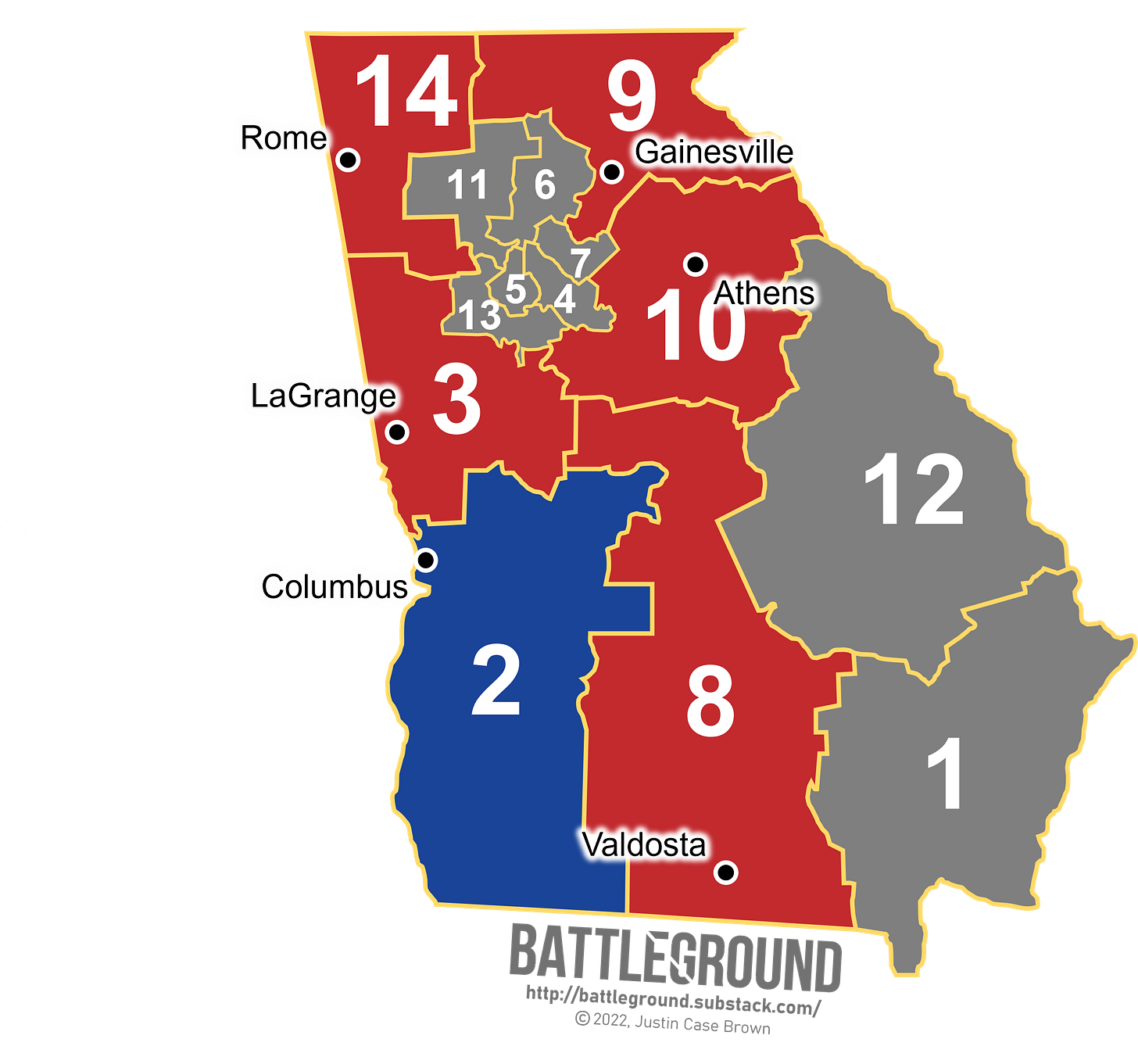

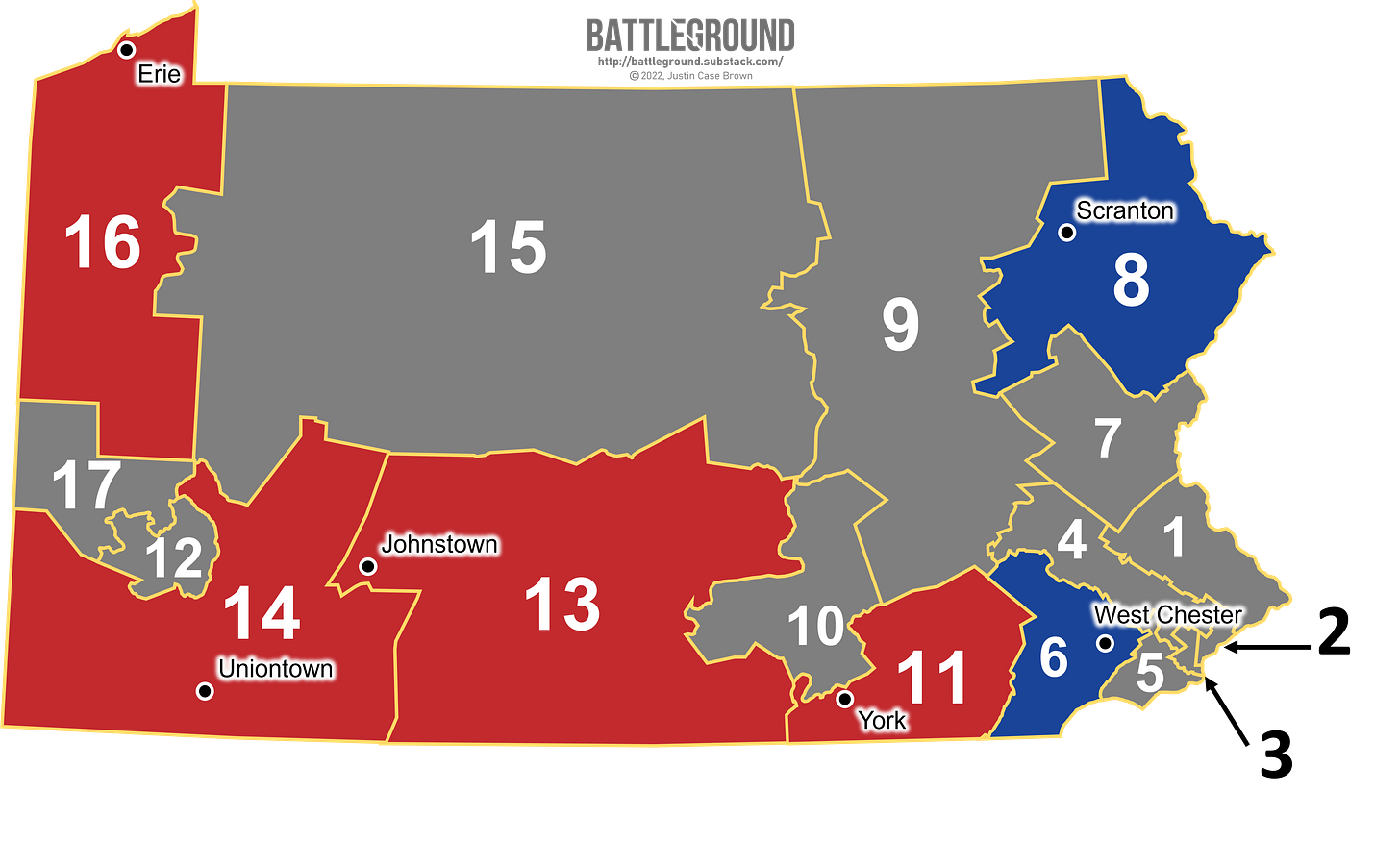

Pennsylvania’s new House district map provides a great example of this racial divide. PA-6 and PA-8 are currently represented by House Democrats and both have double the nonwhite population of their other in-state rural micro counterparts. Meanwhile, PA-14 is the whitest rural micro district in the country: more than 93% of its voters are White. (The other 3 Republican held rural micro districts all have White populations of 85% or higher.)

Micropolitan districts are largely ignored by Democrats and the national media.

Ever read an incisive political profile on La Crosse, Wisconsin or LaGrange, Georgia? (If you couldn’t tell, I love playing the “have you heard of…?” game.) Both of these towns are in pivotal swing states and yet national news outlets often spend more time taking the temperature of voters in and around Milwaukee or Atlanta. This provides an opening for literally anyone who bothers giving attention to these smaller towns. As the Democratic party tends focus its urban approach on larger cities, the Republican party doesn’t need to offer much to court these pivotal voters.

-Wisconsin journalist Dan Kaufman

This feeling of being forgotten has been worsened by the nationalization of local political parties. Nowadays political candidates often eschew a focus on local issues in favor of broader, nationalized topics that often lead to a sharper partisan divide. Jeremy Gragert, a member of Wisconsin’s Eau Claire City Council, explains how these changes shaped his most recent campaign:

The Republican party’s recent populist turn relies heavily on recent changes in our media landscape: it’s much harder to highlight explicitly local issues when less resources are directed toward local journalism. “When local news fades, social media fills the hole,” explains Lewis Friedman, a professor at UW-Madison’s School of Journalism. Conspiracy theories regarding abortion, pedophilia and QAnon can travel much more easily over social media as posts can be micro-targeted to users with compatible ideologies who are less likely to verify the information they encounter. Even the talk radio landscape has shifted toward a focus on nationalized talking points:

Republicans have successfully adapted their campaign tactics to our shifting media landscape which gives them an edge in areas where local media is disappearing. And when you bake in the fact that these districts are less educated than the rest of America (There are only 9 rural micro districts that are considered “average” in higher educational attainment, all others are “below average.”) they don’t need thoughtful solutions to sway their audience. They just need convincing rhetoric that preys on their fears of losing status within American society, like “Make America Great Again!”