Absaroka: The Mount Rushmore State

Leading the nation in natural beauty and coal mines.

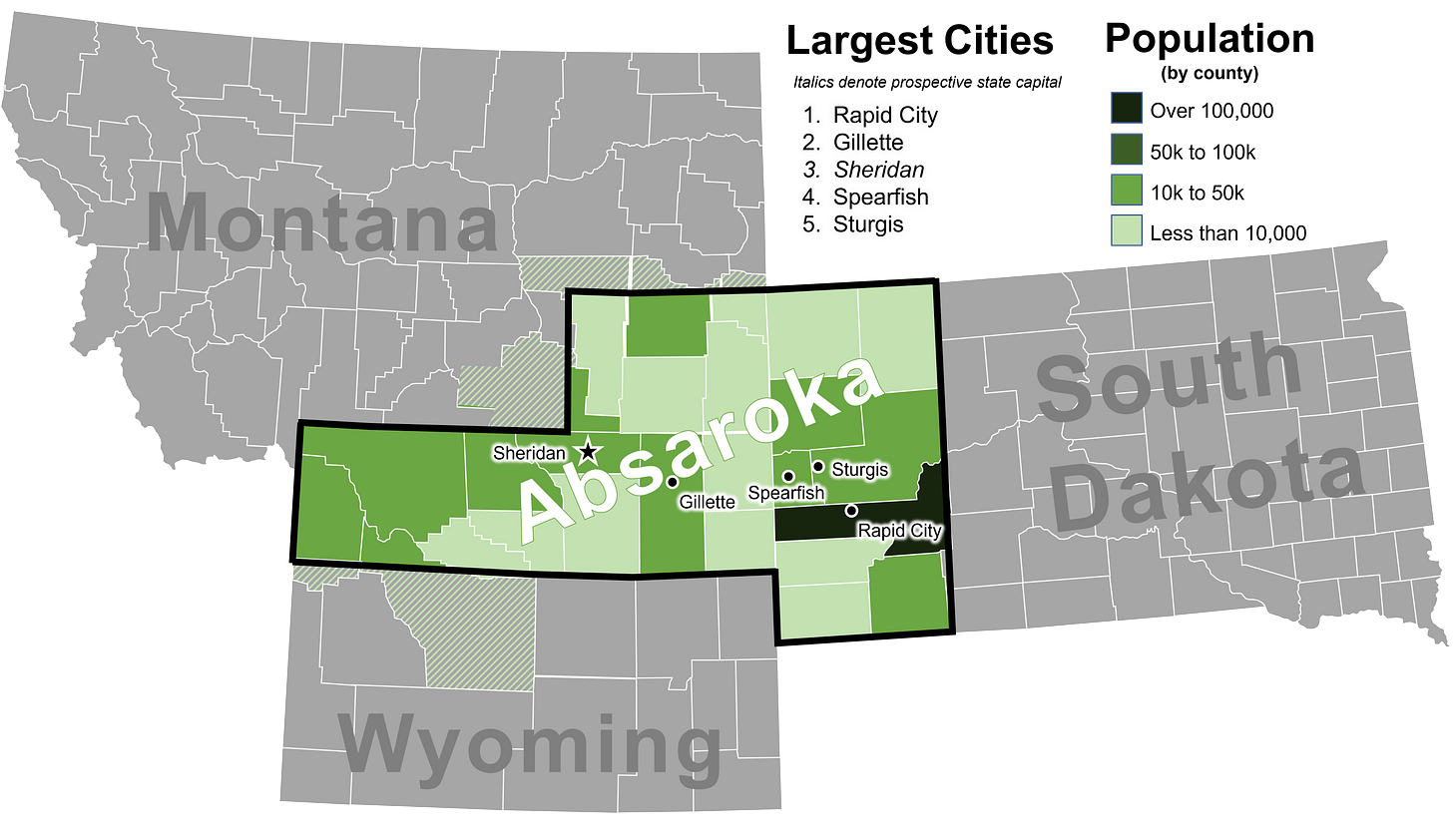

If Absaroka Was A State…

Pronunciation: (ab-SOR-ka)

Total Population: 403,000 residents (~250,000 registered voters)

Prospective State Capital: Sheridan, AB

# of House seats: 1 (Montana would also shrink back down to one seat.)

Major Universities: Sheridan College, Black Hills State University, South Dakota School of Mines & Technology

Notable Attractions/Landmarks: Mount Rushmore, Yellowstone National Park, Bighorn National Forest

Statehood History

In the 1930s, FDR’s New Deal was forcefully reshaping American society in the wake of the Great Depression. Much of this government assistance relied on local institutions to be distributed. Therefore well-connected towns with colleges and hospitals had more access to federal relief while more sparsely populated counties were largely left to fend for themselves.

In Wyoming, this disparity was regional: the southern half of the state saw much federal investment during this time period for a multitude of reasons. Not only was the state capital, Cheyenne, located in the southeastern corner of the state, the transformational Transcontinental Railroad hugged the state’s southern border and was a major economic engine. Democrats from Southern Wyoming dominated state politics and largely ignored the less populated counties in the northern reaches of the state.

By the late 1930s A.R. Swickard, a local street commissioner in Sheridan, Wyoming, was fed up with the ways Democrats neglected the northern reaches of the state. Voters in his neck of the woods generally favored Republicans and cared more about issues related to ranchers rather than industrialists. When looking beyond the Wyoming’s borders into neighboring counties, Swickard found others who shared his same conservative, self-sufficient outlook on government. Above all else, residents living along these state borders wanted an increased sense of self-determination as many felt that their state governments ignored the corners these residents called home.

In 1939, Swickard convened a makeshift statehood convention in Sheridan, Wyoming. He brought together like-minded residents who shared his grievances, drew a map of the potential boundaries and even appointed himself the governor. The state’s proposed name is derived from the indigenous name of the Crow peoples whose reservation lies just northeast of the proposed state. After establishing its borders, secessionist raced to cultivate a regional identity. They held a single Miss Absaroka contest in 1939 to select a beauty queen to represent the state. They even designed a flag that would have nodded to its status as the 49th state admitted into the Union.

Absaroka Today

An important piece of the Absaroka state movement often glossed over was how secessionists saw potential in their proposed state’s natural beauty. In the 1920s, eastern South Dakota became a road trip destination for many Americans as they sought out the natural beauty found in and around the Black Hills. At the same time, legislators in South Dakota were seeking to build a Shrine of Democracy etched into its mountains to further lean into this tourism boom. The Absaroka statehood movement intersected almost perfectly with the construction of Mount Rushmore as the president’s faces were finally completed in the same year secessionist drew their map. (Fun fact: Mt. Rushmore was supposed to depict each president down to their waist. This was abandoned after funds dried up in 1941.) The proposed boundaries not only placed Mt. Rushmore squarely inside the boundaries of Absaroka, they also included Yellowstone National Park, truly making the state the “nation’s playground.”

In the moment of the movement, much attention was paid to those who tilled and maintained the region’s grasslands to sustain themselves. Residents coalesced to defend the rancher lifestyle that was often looked down upon and misunderstood by cosmopolitan decision makers confined to the coasts. While ranching would have been a major aspect of the proposed state’s economy, the coal industry that has since emerged in this region would have been the primary driver of Absaroka’s economic growth. The proposed state would hold almost the entirety of the Powder River Basin which is the largest source of low sulfur coal in the nation and holds 8 of the nation’s 10 largest coal mines.

While the secessionist movement was snuffed out with the onset of World War II in 1941, the political fault lines that created the secessionist movement still exist today. South Dakota’s political landscape is still split by the Missouri River, with would-be-Absarokans in counties to the west voting more heavily Republican than those to the east. The same goes for Montana and Wyoming: counties included in Absaroka continue to vote more Republican than those that were not. While the Absaroka statehood movement hasn’t been resurrected since, it’s regional identity lives on.