While we tend to focus on voting rights and ballot access through the lens of African Americans, Indigenous peoples also have a long history of voter disenfranchisement that persists to this day. I want to use these final few posts to raise this issue, among many others that Native Americans are facing today in their communities. Their experience with racism parallels the Black American experience as the forced relocation, social isolation and political exclusion of Indigenous peoples across America was perpetrated by the state. Remedies are necessary and the extensive documentation of past injustices against Native Americans can help provide us with a path forward.

Let’s begin with the state with the largest proportion of Indigenous residents: Alaska

Topline Takeaways

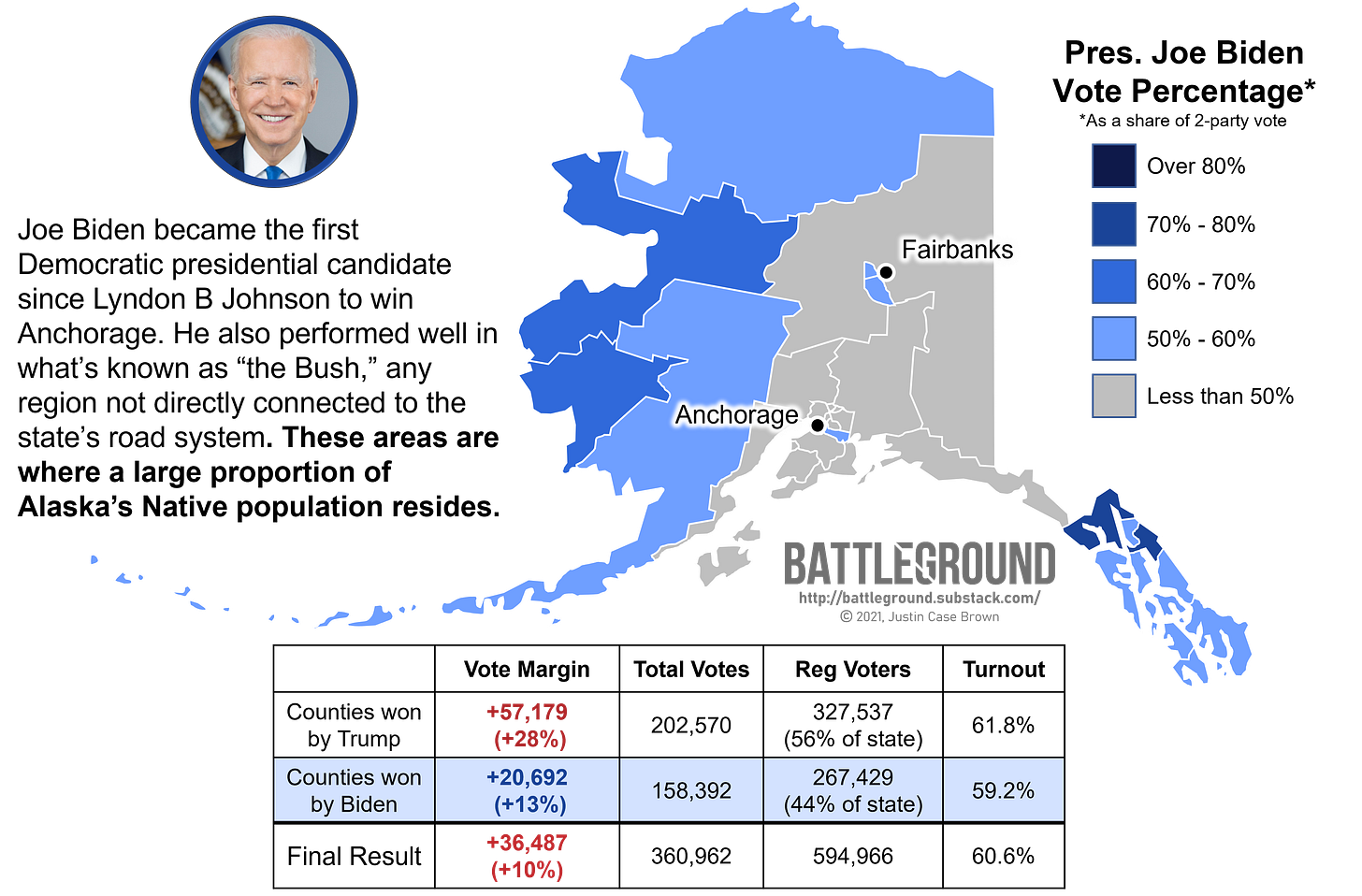

Alaska became more polarized between the 2016 and 2020 elections. Areas won by Clinton in 2016 saw higher margins for Biden in 2020 while the Interior region broke more strongly in favor of Trump in 2020.

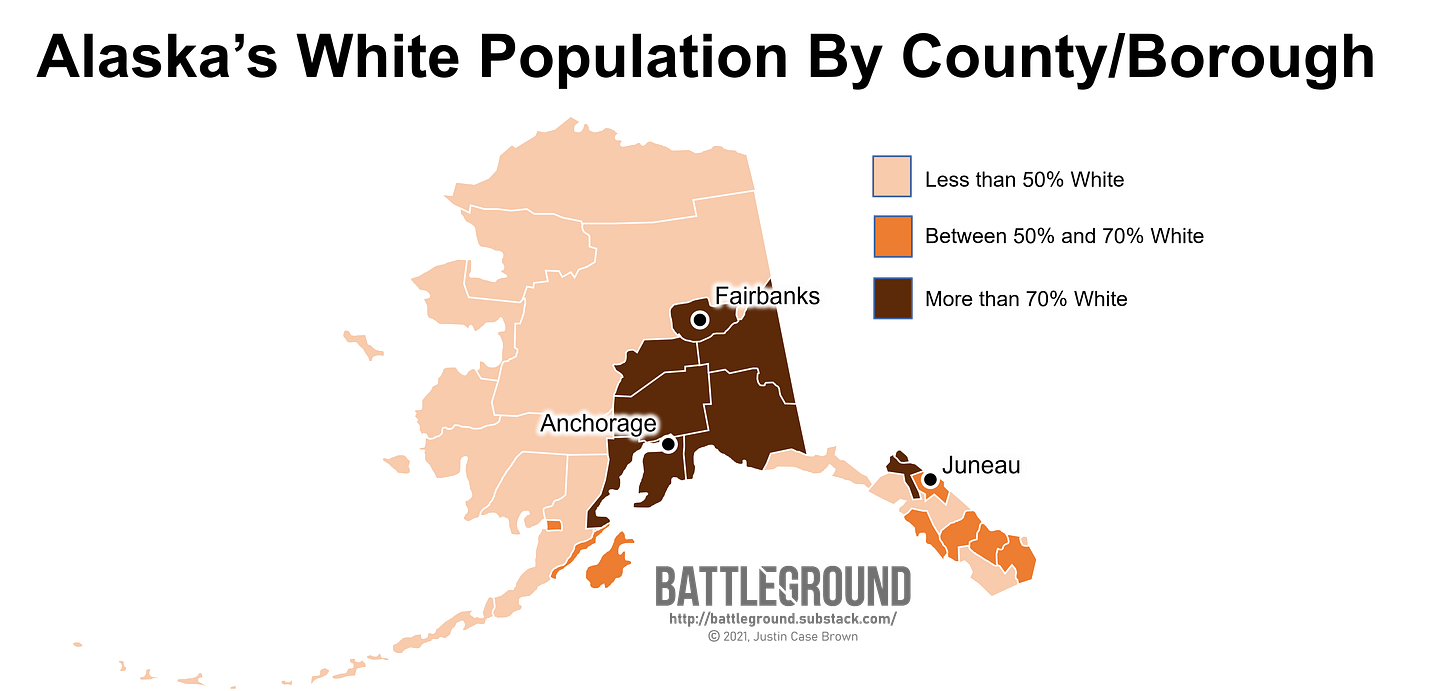

Alaska’s electoral geography is shaped by its racial geography: areas with high White populations regularly vote for Republicans whereas regions with high proportions of Alaskan Natives typically support Democrats.

While Alaska has the largest proportion of Indigenous residents of any state within the US, disenfranchisement of the Alaskan Native population continues to be a significant problem to this day.

In-Depth Insights

Donald Trump won Alaska for a second time, continuing Alaska’s streak of voting for every Republican presidential candidate since 1968. His strength comes from the predominately white areas of the Alaskan Interior where he won the city of Fairbanks. While Joe Biden ran on a pledge to reduce emissions by reducing the size of the domestic oil and gas industry, Trump promised to expand it. The petroleum sector is a critical driver of Alaska’s economy, supplying the state with roughly 30% of its jobs. The Republican party also aligns well with many Alaskan voters’ commitment to the Second Amendment as nearly two-thirds of Alaskan adults own a gun. Altogether, the Republican party platform is particularly attractive to the state’s White population and as a result the whitest areas of the state regularly break toward the GOP.

However, it’s important to note that this geography is no accident. Alaska has the largest Indigenous population within the United States, currently sitting just above 15%. But the United States’ settlement and annexation of Alaska was marred with racism. Gold rushes in the early 1900s convinced White American settlers to make the long trip up north and the region was officially recognized as a United States territory in 1912. As settlements in the area grew, Indigenous peoples were met with epidemics on initial contact, social segregation, forced relocation and political exclusion.

Joe Biden performed most strongly in the more diverse areas of the state where Alaskan Natives makeup a higher proportion of voters. Much of this is known as “the Bush” as these are areas not directly connected to the state’s road system. One major reason why Biden was able to gain ground in these areas was his opposition to the Trump administration’s relaxing of climate policies which included increased drilling and mining in the Alaskan wilderness. Further industrialization in these areas could devastate the ecosystems that many Alaskan Natives rely on for sustenance. In addition to the state’s hinterlands, Biden also became the first Democrat to win Anchorage, the state’s largest city. Despite this win, Biden’s more multicultural coalition was not large enough to overcome Trump’s and this is due, in part, to Alaska’s long history of voter disenfranchisement.

Early efforts to curtail the political participation of Indigenous peoples began with their exclusion from citizenship. Alaska’s 1915 Territorial Act explicitly denied citizenship to Alaskan Natives unless they denounced “any tribal customs or relationship” and adopted the habits of “civilized life.” While this provision was axed in 1924 with the passage of the federal Indian Citizenship Act, Alaska’s legislators acted quickly to keep the Indigenous peoples “in his place.” In 1925, led by Alaskan Republicans, the legislature instituted an English literacy test as a part of the voter registration process. The newspaper ad captured above was commissioned by the Alaskan Republican Party and lays bare their clear racist intent. This literacy test was enshrined in the state constitution when Alaska was admitted to the union in 1959 and was not repealed until 1970, five years after the Voting Rights Act was passed.

After the literacy test was repealed, a large proportion of Alaskan Natives still struggled to vote since registration and ballot materials were only printed in English. (Over twenty different languages are spoken by Indigenous peoples across Alaska.) This still served as a de-facto literacy test and was meant to be addressed with the extension of the Voting Rights Act in 1975. The extension was designed to identify minority language populations across the country and mandate that these jurisdictions provide ballot materials in other written languages to increase access. Unfortunately, the focus on “written languages” created a loophole where Alaskan legislators did not have to comply with the law as many of the different languages spoken by Alaskan Natives are oral and have no written history.

This language-based exclusion persisted for decades: in the 2008 presidential election, turnout for Alaskan Natives was 20 percent lower than the overall statewide turnout. As a result, the ACLU partnered with tribes from Bethel, Alaska and sued the state for failing to provide adequate election materials for speakers of the Yup’ik language. After years of litigation, the state of Alaska settled in 2010 and agreed to furnish oral translators and poll workers who were fluent in the language. The problem persisted though for all other language communities as the state only instituted the language remedies for those within the Bethel Census Area. Alaskan Natives sued the state again in 2013, alleging that Alaska continued to exclude language minorities from the ballot box and submitted the state’s English-only “Official Election Pamphlet” as evidence. The courts ruled again in the favor of Alaskan Natives and ordered the state to supply language resources that were compliant with the Voting Rights Act.

Forecasting the Future: Alaskan Natives still encounter numerous barriers to voting that hamper their electoral power. While Alaska has made progress on supplying the necessary materials to enfranchise people of all language backgrounds, disparities remain. Further compliance audits have found that Alaska is still not in compliance with the Voting Rights Act. In the 2016 election, auditors found that less than half of poll workers received the proper federally mandated training and that training was conducted exclusively in English by a non-Native speaker. In addition to the language barrier, Alaska’s difficult and expansive geography makes it difficult for voters in the Bush to access polling locations. Studies have found that numerous tribes are so isolated that they are forced to take a plane or a boat to cast their ballot, a journey too expensive or untenable for many. Even voting by mail is difficult for many Alaskan Natives as most do not have their own mailboxes and have to make long journeys to the closest post office. While these geographic barriers will always exacerbate the ease of voting, the state has dragged its feet throughout its history in efforts to ensure all Alaskan residents have the ability to vote. As a result, the electoral landscape continues to favor Republicans as their voters are significantly more likely to have access than many Democratic voters.

Leftover Links

Check out an even deeper dive into a full historical review of Alaskan Native voting rights.

The 2021 Native American Voting Rights Act was introduced to the Senate in August and seeks to provide equal access to the ballot for all Indigenous peoples within the United States.

Interested in supporting the cause? Consider donating to the Native American Rights Fund.