Is Ohio Republican or Democratic?

Shifts in the Buckeye state have challenged pollsters in recent years.

Topline Takeaways

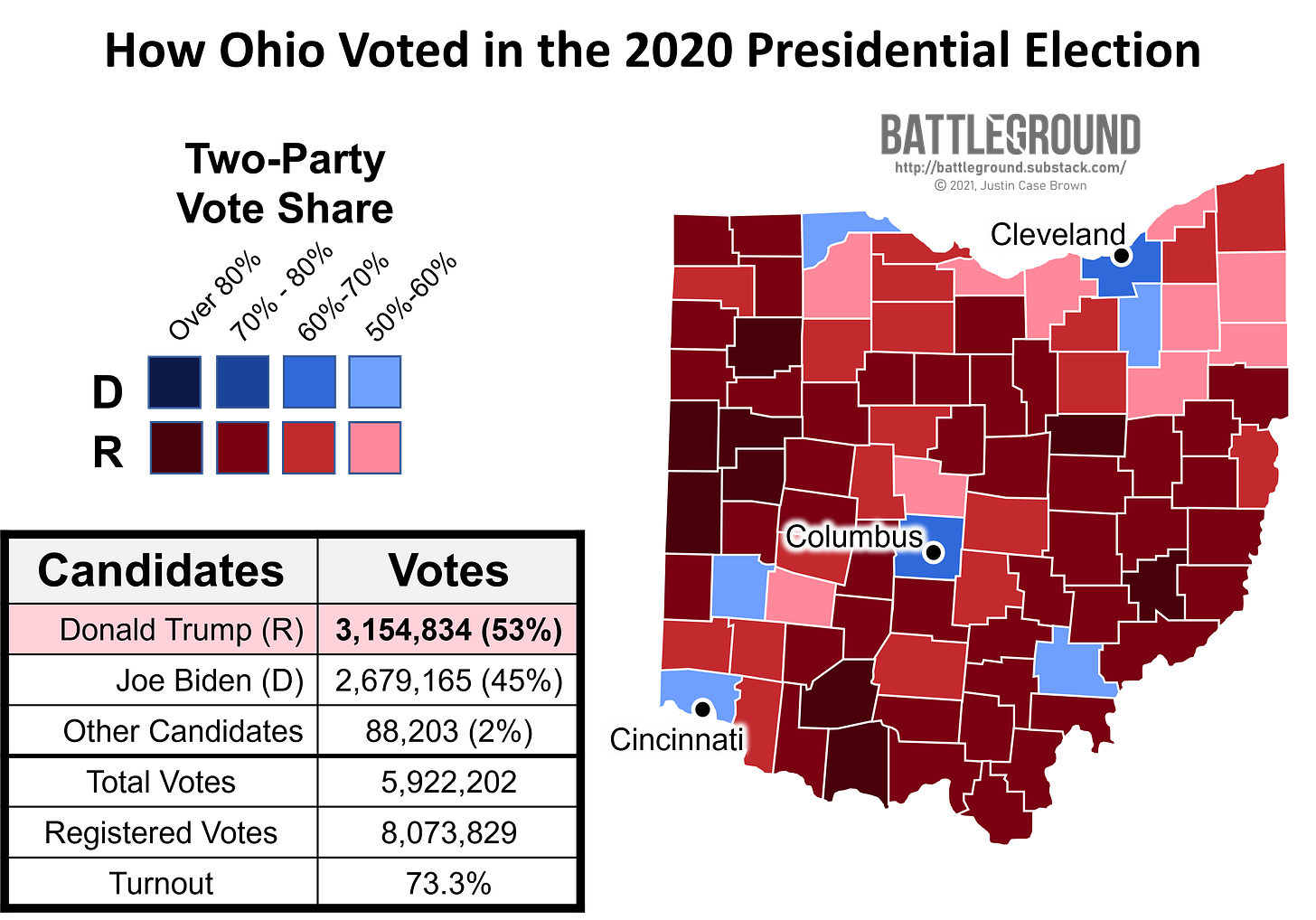

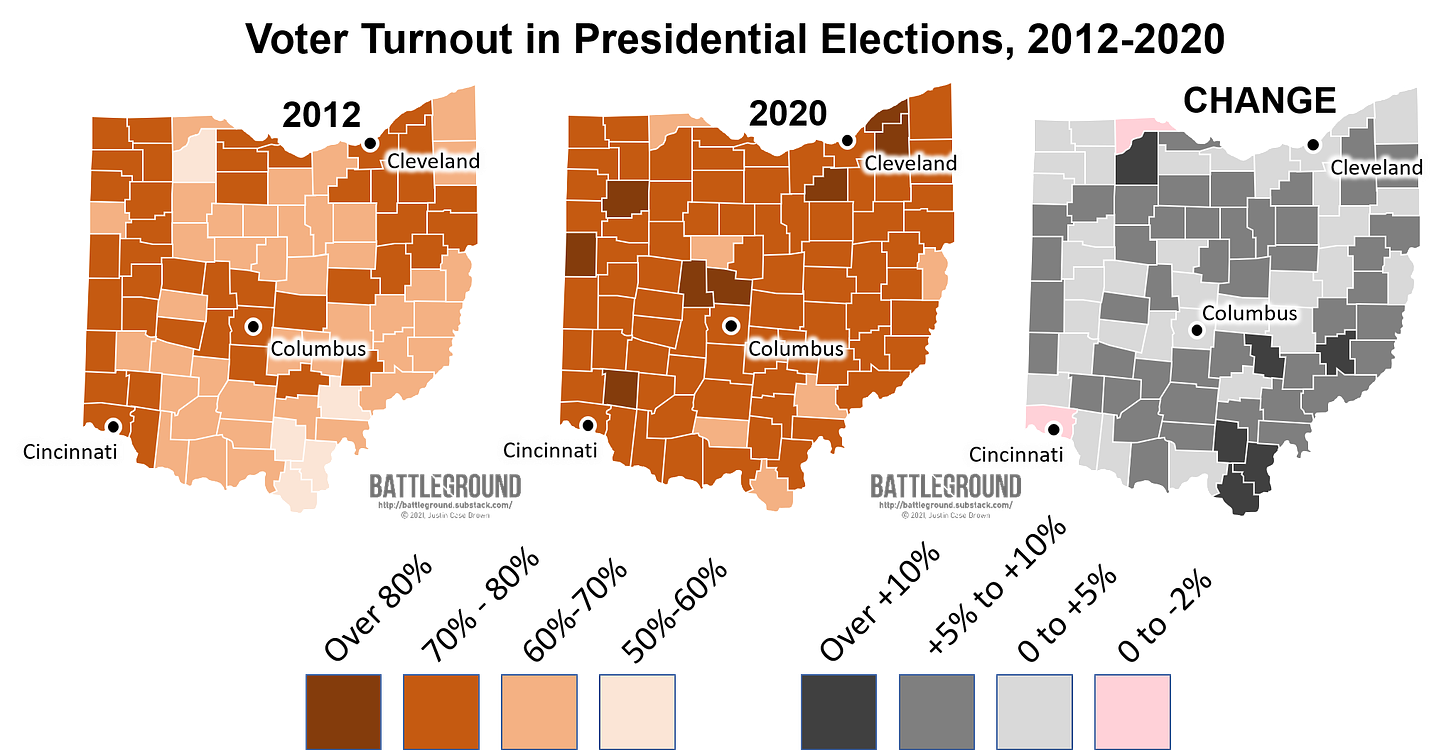

Both presidential candidates focused on turning out their base: Biden in the “Three C” cities and Trump in the rural areas in between.

Disengagement and deterrence of Black voters worked against Democrats, shifting the electorate in favor of Republicans.

As the state moves further to the right of the rest of the nation, many have a hard time predicting election results as the shift is due to a changing electorate, rather than a shift in public opinion.

In-Depth Insights

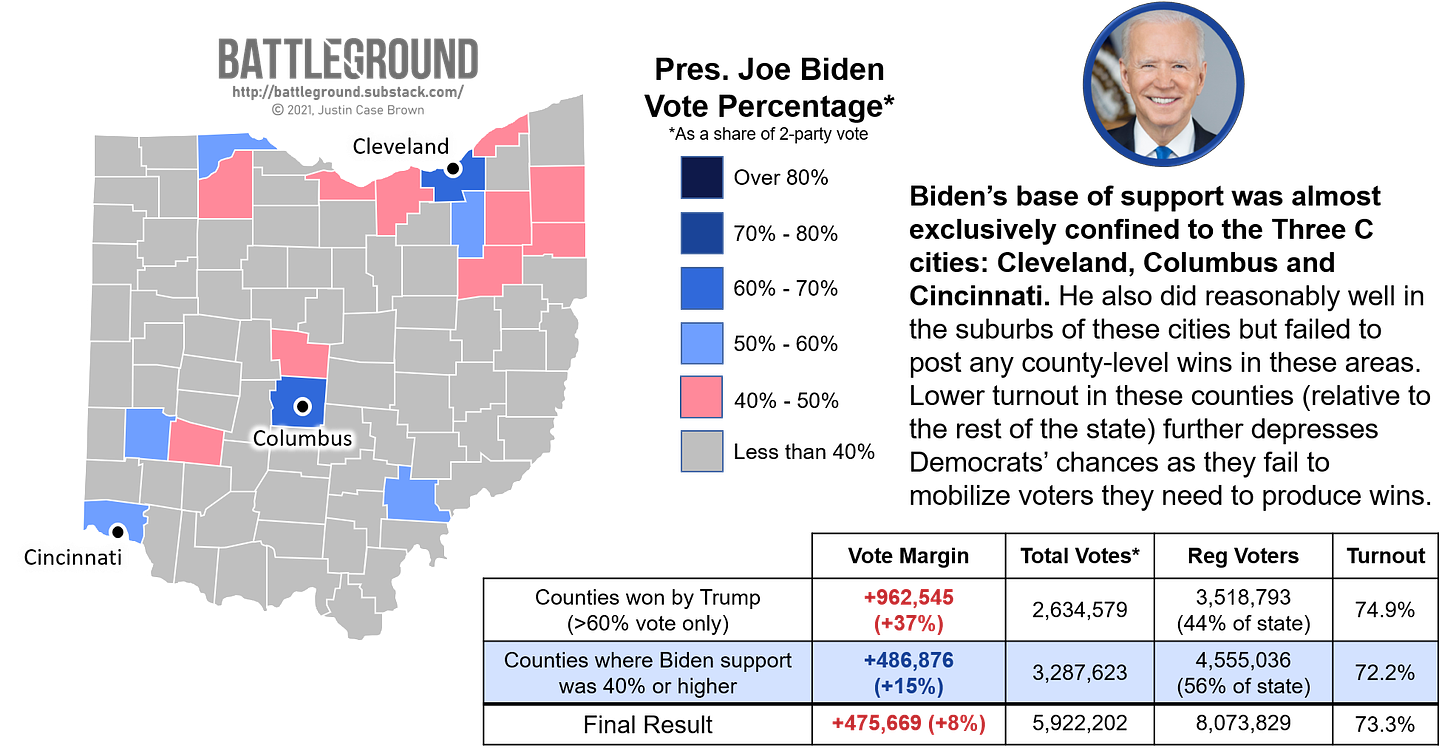

Biden’s voting base is almost exclusively confined to urban environments in Ohio. The Democrat won each of the counties home to the “Three C’s”: Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati, yet these three metros saw some of the smallest gains in turnout over the past decade compared to the rest of the state. In the map above, I included counties where Biden lost but garnered at least 40% of the vote as it illustrates Biden’s success at keeping the margins close in neighboring suburban areas.

One major reason behind Democrats’ struggles in the state has been the disengagement of Black voters following Barack Obama’s campaigns. In 2012, exit polls estimated that roughly 15% of Ohio’s electorate was made up of Black voters, that fell to 11% in 2020 exit polls as White voters participated in larger numbers.

To be very clear, this isn’t simply Black voters passively choosing to sit out of elections. A report (from Britain of all places) found evidence that the Trump campaign used a database of information on 3.5 million Black voters with the specific goal of deterring them from voting. The result: Black turnout in the state dropped for the first time in 20 years.

The disconnect is also due to strategies employed by the Ohio Democratic party, a group that has embraced a strategy of appealing primarily to White voters in order to regain competitiveness in the state. Not only has this strategy failed to produce meaningful success, it has also eroded trust in the Black community.

“There is this disconnect, especially with white elected officials, who don’t take the concerns of Black voters at face value… You should be expanding the electorate to people who will vote for you. It’s less expensive to do turnout votes than persuasion votes. But for some reason, the party is hellbent on focusing their resources on voters who have clearly said this is not the party they want to be a part of.”

- Emilia Sykes, the Democratic minority leader of the Ohio House of Representatives

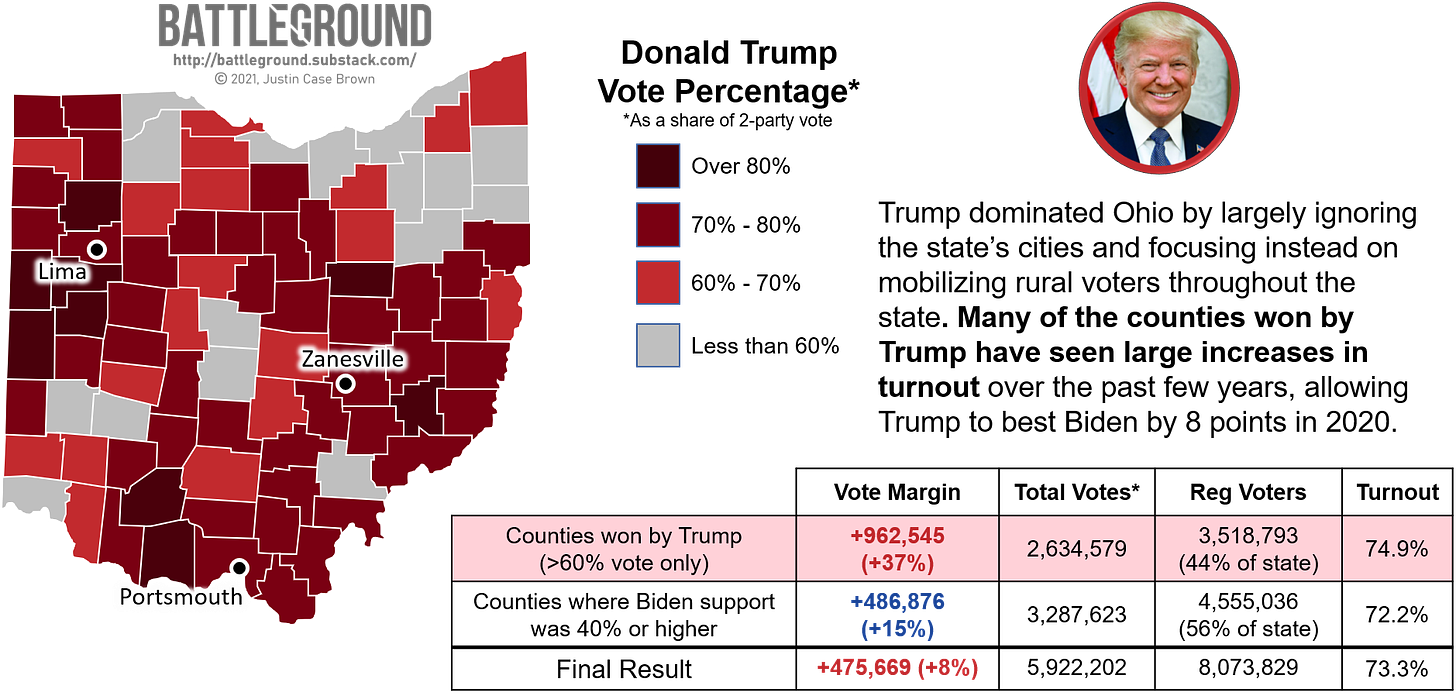

Donald Trump won Ohio by embracing the same strategy Emilia Sykes wants Democrats to employ: turning out the vote among his base. He failed to win the state’s most populous counties and posted relatively tight margins in some of the state’s suburban counties but these trends were dwarfed by large increases in turnout in just about every county he won. When looking at the changes in voter turnout over the past decade, many of the counties with the largest changes in turnout were counties where Trump won more than 70% of the vote.

Forecasting the Future: Despite ultimately tilting toward Trump by eight points, Ohio was rated by many polls as a toss-up state, predicting a much closer race and significantly less support for the Republican candidate. Analyzing the aforementioned changes in the electorate is key to predicting how Ohio votes in future elections and explains why pollsters have been so off in recent years. Let’s first acknowledge the abnormality of the 2020 election: Donald Trump can’t take all of the credit for driving turnout during this cycle as the pandemic forced most states to change their election procedures, resulting in historic participation across the nation. (Ohio beat it’s previous record for voter turnout last established in 2008.) Pollsters naturally had an incredibly difficult time predicting how these changes might affect voting behavior.

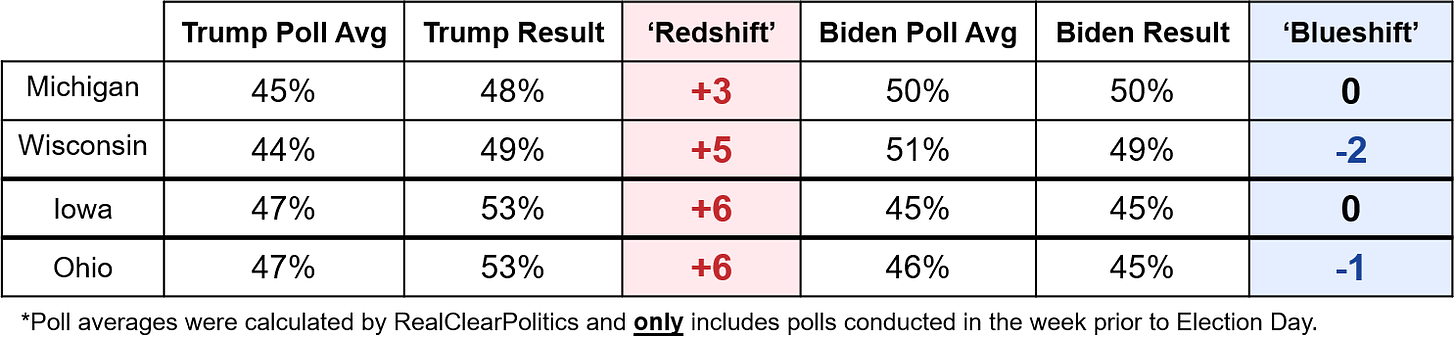

But pollsters predicted Biden’s level of support surprisingly accurately: his polling average in Ohio during the week leading up to Election Day was literally one point off from the final result. It was very specifically Donald Trump’s level of support that they had such a difficult time estimating: the polling average was six points off in estimating support for Trump, even the reputable Quinnipiac poll was off by nearly 10 points in both of its Ohio polls conducted in the week leading up to election day. This error was prominent across Midwestern swing states. The primary driver of this ‘redshift’ is that pollsters did a horrible job at accurately predicting who would show up on Election Day.

It’s a widely shared hypothesis that Trump voters are much less likely to respond to polls, leading researchers who are conducting these polls to “weight” responses from self-identified Trump voters more heavily. As such, researchers are forced to make more assumptions about what Trump voters look like than for Biden voters who are easier to reach. Hold on to that thought.

Let’s also consider that most of today’s polls are run by universities or mainstream media companies; organizations that typically lean heavily toward liberalism. Meanwhile, voters across the Midwest have been trending in the opposite direction, voting to the right of the rest of the nation in both the 2016 and 2020 elections. I use the term ‘redshift’ because the dynamics of this phenomenon match up with the term’s scientific definition. In physics, redshift occurs for the viewer when the source of light is moving away from the observer. In politics, many voters in the Great Lakes region are moving away from these poll observers on the political spectrum, meaning that the assumptions many pollsters make to properly estimate the electorate are increasingly incorrect.

The 2008 and 2012 elections created a false reality among many educated Americans separated from rural areas. The fact that rural voters in states like Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, hell even Indiana, voted for a Black president was a sign for many political elites that America was officially a post-racial society. That contributed to the shock of the 2016 election as many polls foolishly expected Black turnout to be close to levels seen during the Obama years and underestimated the effects of both voter deterrence and voluntary disengagement.