West Virginia: Landowners v. Residents

Soooo this one's a bit awkward for Joe Biden...

Topline Takeaways

Due to West Virginia’s historical reliance on resource extraction, much of its land is owned by private corporations which shifts political power away from residents.

With their embrace of environmentalism and the vilification of coal-related pollution, Democrats have largely alienated West Virginian voters and have yet to win a single county in a presidential election since 2008.

Voters in the state are struggling as they face mounting health problems and a raging opioid epidemic. Yet they support Republican candidates that often maintain the status quo rather than upsetting the current balance of power.

In-Depth Insights

Believe it or not, West Virginia was once a relatively competitive state where Democrats had a voice. The state’s recent flip to a deep red hue is best understood by reviewing its economic history in the context of today’s political parties.

Much like Kentucky, West Virginia’s economy relies heavily on resource extraction and is one of the largest coal producers in the United States. The landscape is very rugged with the Cumberland Plateau in the east and the ridge-and-valley region to the west. The completion of several railroad systems in the mid-1800s led to substantial population growth: increasing at least 20% every decade throughout the 19th century. Despite the expansion of transportation, most Appalachian mines (and thusly miners) remained isolated in the early 1900s. This led the mining companies to create company towns, often called “coal camps.” These small towns were frequently built at the base of a mine and included cheaply made houses, a school, a church and a company store. While at first this seemed like a benevolent way for companies to improve the livelihoods of their workers, the practice morphed into a method of controlling residents as county and state governments largely relinquished their governing authority to the landowning coal companies.

By 1920, nearly 80% of West Virginians lived in company houses, meaning the vast majority of residents did not own the land they lived on. To make matters worse, miners were often paid in “scrip” instead of cash; company tokens that were only accepted at the town’s company store. This often further isolated miners as their income was not widely accepted in neighboring towns run by different companies and forced families to stay local, preventing workers from building transferable wealth. The local company store was often the only commercial enterprise in town, allowing owners to charge exorbitant prices that residents had no choice but to pay. By the time this practice was outlawed in the 1950s, much of the wealth built from coal mining was already extracted out of the state, sent off to the owners of the coal companies who lived far away from the mines in other areas of the US. The miners themselves incurred the costs of the business in the form of adverse health outcomes derived from a mixture of heavy pollution and the back-breaking labor required in the mines.

During the mid-20th century, federal labor laws improved, leading to the rise of labor unions. Organizations like the United Mine Workers of America fought against exploitative practices and succeeded in bolstering workplace safety standards and increasing wages. This coincided with the postwar energy boom which transformed difficult labor into coveted, well-paying jobs that provided hope and prosperity to struggling families.

This background is essential to understanding how West Virginia votes today as many families with ancestral ties to mining jobs still view resource extraction industries like coal mining as their ticket to attaining the increasingly elusive American Dream. The reality on the ground is that the continued reliance on these companies does families more harm than good, as they’re forced to deal with ever-increasing health issues, subpar healthcare and inadequate wages. The extractive nature of the industry is by design: whether it be timber, coal or natural gas, wealthy out-of-state landowners are the primary decision makers for much of West Virginia. Not only does this restrict the landowning ability of the average West Virginia resident, it also increases the political influence of corporations and decreases civic engagement. This can still be seen today in the form of low voter turnout: even in the historic 2020 election, West Virginia had one of the lowest voter turnouts in the nation, almost 10 points behind the national average.

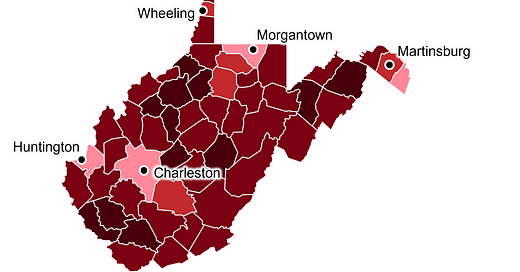

Again, much like Kentucky, West Virginia had a long history of voting for Democrats. That changed in the 2000s when the national Democratic party embraced environmentalism and began fighting against many of the state’s major landowners. Meanwhile, Trump rose to power on promises to bring back the glory days of coal. The state’s voters followed him in droves, turning to Republicans who vowed to keep the state’s economy stable by retaining the status quo. With this background it’s no coincidence that every county in West Virginia voted for Trump in both the 2016 and 2020 elections.

Forecasting the Future: Democrats failed to capture a single county in the state for a third election in a row. While Democratic grassroots efforts are emerging in some of the state’s towns they often go ignored by a national party who sees West Virginia as a lost cause. Also playing against Democrats are the state’s demographics: the population is overwhelmingly White, with over 90% of its residents identifying as such.

Meanwhile, Governor Jim Justice embodies both the history and future of West Virginia. He has a net worth of over $1.2 billion making him the state’s wealthiest resident. His wealth is amassed from a multitude of businesses, all of which spur from a vast amount of land inherited from his father. Not only does Justice run the family’s coal business, he also founded Bluestone Farms which is known as one of the largest grain producers on the East Coast. Like many voters in the state, he is a former Democrat turned Republican, in part spurred by Donald Trump’s favorable view on keeping coal industries afloat.

The true test for West Virginia Republicans lies in their handling of the state’s struggles amidst a national opioid epidemic. Many miners have fallen into the addictive spiral of opioid abuse, often spurred by receiving painkillers necessary to blunt the pain brought on by injuries from taxing, physical labor.

A quote from Isador Lubin, author of Miners’ Wages and the Cost of Coal, brilliantly illustrates the problem West Virginia is facing: “The operator sold his men rather than his coal.” Landowners and corporate executives have built massive caches of wealth and power on the backs of their workers. But what happens when their backs break?