Alabama: The Gerrymander That Wasn't (then was again!)

Racial gerrymandering is alive and well in the American South.

Topline Takeaways

Alabama’s new congressional map was drawn and passed almost exclusively by Republicans in the state legislature.

A federal district court struck down the new map for racial gerrymandering due to the way it dilutes Black electoral power by packing most of the state’s African American voters into a single district. The state appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court and the Court decided to hear the case. The Supreme Court has ruled that the map does employ racial gerrymandering and the state is required to enact a new map that provides two minority-majority districts.

This map likely wouldn’t exist if Alabama was still subject to the federal preclearance requirement in the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Supreme Court struck down the preclearance formula in 2013, meaning this is the first redistricting cycle since the 1960s in which Alabama has minimal federal oversight on its redistricting process.

Who’s In Control?

In Alabama, the legislature has almost complete control over the redistricting process. A new congressional map is drawn and passed by the legislature and sent to the governor for approval. If the governor vetoes the new map, it only takes a simple majority vote to overturn a gubernatorial veto.

Alabama was previously subject to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and was freed from this restriction in 2013. Commonly known as the “preclearance requirement,” it prevented governments in certain states and counties from implementing any changes to voting laws without receiving approval from either the US Attorney General or the US District Court for DC. Section 4(b) contained a “coverage formula” that was used to determine which jurisdictions would be subject to preclearance. Any county or state that failed the following conditions was subject to preclearance:

As of November 1, 1964, 1968, or 1972, the jurisdiction used a "test or device" to restrict the opportunity to register and vote; and

Less than half of the jurisdiction's eligible citizens were registered to vote on November 1, 1964, 1968, or 1972; or less than half of eligible citizens voted in the presidential election of November 1964, 1968, or 1972.

This provision was used to prevent democratic backsliding of voting rights for close to 50 years and applied to a variety of states like Virginia, Alaska and Arizona as well as individual counties in New York and California. Section 5 is now largely unenforceable after the formula used to determine which jurisdictions required preclearance was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.1

District Breakdown

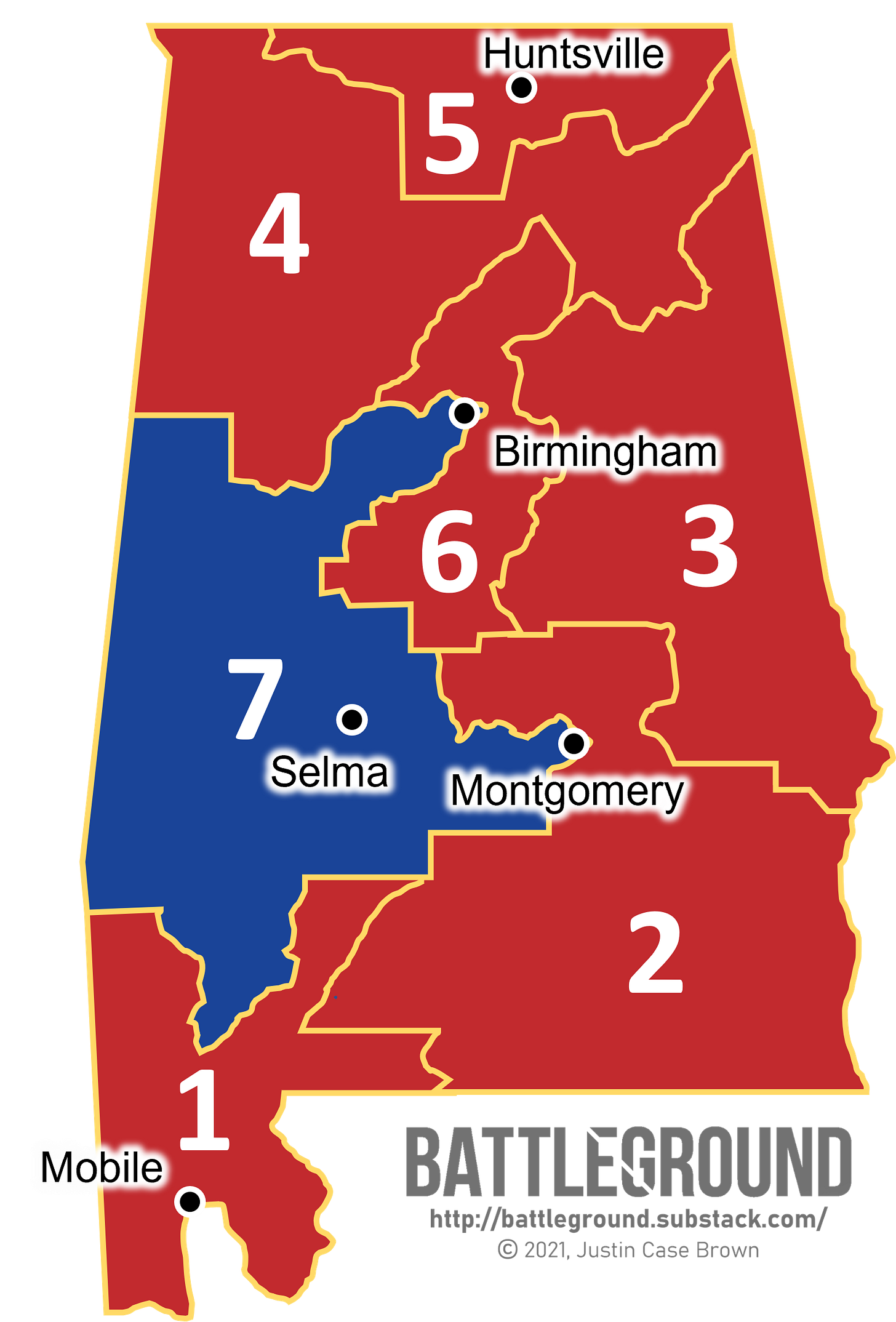

Alabama’s congressional map (allegedly) disenfranchises the state’s Black voting base. About 27% of the state’s population identifies as African American, therefore accurate representation would mean that Black voters would have electoral control of two House seats in a seven-seat state. (2/7 = 28%, an almost perfect match to the size of the state’s current Black population). Instead, lawmakers drew a map that packs the bulk of the state’s Black voters into a single district that is less safe than its previous configuration. (The new AL-7 sees a shift of 10 points toward Republicans despite still leaning toward Democrats.) It also stretches the definition of a “compact district” due to the way it reaches into the Black neighborhoods of Birmingham and Montgomery while completely avoiding the towns that lie between the two cities along Interstate 65. (Hint: That’s because those towns are overwhelmingly White.)

On January 24th, a federal court struck down Alabama’s new congressional districts and agreed that the new boundaries gave Black voters too few opportunities to elect a candidate of their choice. The court explicitly demanded that any acceptable alternatives “will need to include two districts in which Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it.”

Doubling Down

Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall appealed the federal court decision to the US Supreme Court in hopes that the nation’s highest court will let the map stand as is. Not only has the Alabama Republican party fully supported the motion, 14 states filed a joint brief in support of Alabama’s case. It should be of no surprise that the bulk of the state AGs supporting the case are from states that were previously subject to preclearance requirements like Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Arizona and Texas.

The Supreme Court has decided to take up the case and will hear arguments regarding the constitutionality of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The Court has put a stay on the lower court’s ruling, upholding the map for the 2022 election cycle.

Despite the fact that the original preclearance formula was struck down by the Supreme Court, there were a small handful of jurisdictions across the country that were “bailed-in” to a preclearance requirement due to their violation of a different provision of the VRA. Section 3 provides its own language to govern preclearance, allowing for courts to demand any jurisdiction found violating voting guarantees in the 14th or 15th amendments to be subject to federal oversight of voting law changes. Since the Supreme Court only struck down Section 4(b), Section 3 can still be used to enforce preclearance requirements. The specifics of Section 3 preclearance are determined by the courts at the time of the “bail-in” and is not a standardized “blanket” requirement like Section 5. Check out this in-depth critique from the Columbia Law Review on why Section 3 preclearance is “rarely used.”