Topline Takeaways

North Carolina’s historical east-west divide has largely eroded, as many eastern counties that were once Democratic strongholds are now voting for Republican candidates.

An urban-rural divide has replaced the east-west divide and is more predictive of how counties will vote.

Growth in the Piedmont Urban Crescent will likely determine future electoral prospects for both parties, possibly giving Democrats a slight edge in upcoming elections.

In-depth Insights

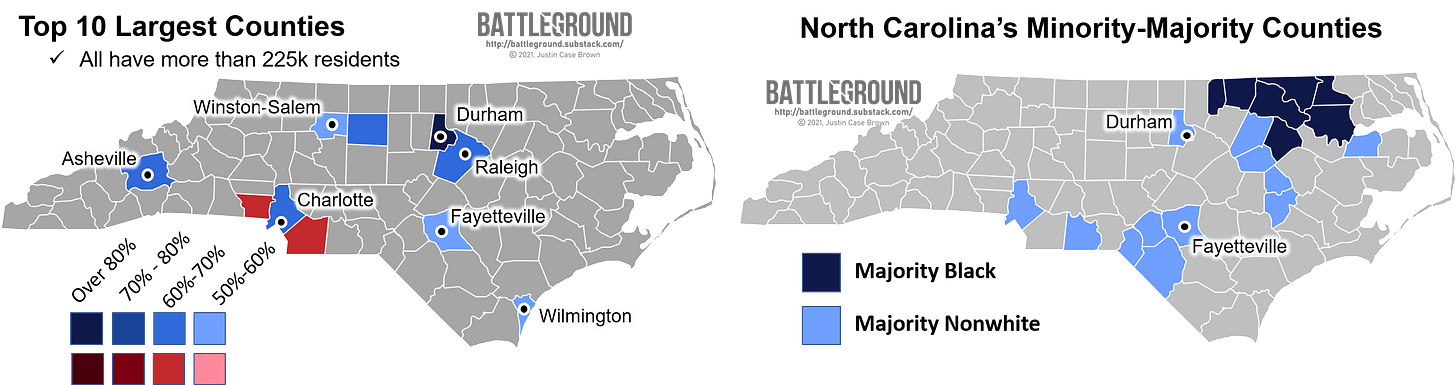

Biden’s base in North Carolina sits firmly in urban counties distributed throughout the state. Whether it be beachy Wilmington on the coast or leafy Asheville in the mountains, Democratic strength in the state is currently confined almost exclusively to urban environments. The exception to this rule lies in the northern reaches of the Black Belt: a cluster of counties bordering Virginia where African Americans make up the majority of voters. Counties in this area are some of the final rural Democratic holdouts in the North Carolina’s coastal plains. (In the late 20th century Democrats won much larger swaths of eastern North Carolina, peaking with Jimmy Carter’s candidacies in 1976 and 1980.)

The rural shift away from Democrats holds many of the same qualities as other parts of our country. As industries like textiles and tobacco began to shrink, voters felt that Democrats turned their back on residents that relied on these jobs. “They just felt like Washington had forgotten them,” says George Daniel, an attorney in the state’s mountainous western region. Many of these areas are also infamous “Obama-Trump” counties, places that once supported Pres. Obama but immediately flipped to supporting Donald Trump in 2016. One voter identified the unifying quality between the candidates as seen by those on the ground: “The message of both Obama and Trump boiled down to economic hope,” and in 2016 “when they heard ‘Clinton,’ they heard NAFTA… A lot of the older workers (in Robeson) considered NAFTA an unforgivable move by the federal government.”

But that doesn’t mean all of these voters have blindly embraced Trump as a replacement; some voters don’t see Trump’s approach to trade as successful either. “I think having huge trade wars is not effective, and I think also having no trade policies where we’re trying to compete on an unlevel playing field is also unfair.”

Republicans have been carefully walking a tightrope in North Carolina for decades. Over the last thirty years, Republican candidates have won seven out of eight presidential elections in the state (the exception being Obama’s historic candidacy in 2008.) Despite this perceived dominance, six elections were decided by a margin of less than five points. North Carolina is surely a swing state; what’s most fascinating is the dynamic nature of its electorate. Throughout the state’s history, North Carolina has held a cultural divide between the coastal plains in the east and the mountain ranges in the west (the split even colors debates about the state’s approach to BBQ.) Much of this divide can be traced back to slavery: the eastern regions where slavery was profitable held significant political and economic power, whereas the more rugged western regions were harder to navigate and establish large settlements, making slavery mostly unprofitable. (Although to be clear, slavery still existed in the mountains, it was just nowhere near as prevalent as counties in the east.)

The two halves of the state relied on differing economies for much of the 1800s. While these differences began to erode in the early twentieth century with the ending of slavery, the political effects of this rivalry stood strong for decades: eastern counties with higher African American populations supported Democrats while western counties with primarily White populations were reliable Republican strongholds. This dynamic stood firm until the Republican Party began embracing the “Southern Strategy,” causing White rural Democrats to switch parties in droves. As a result, the east-west dynamic that was once readily apparent on North Carolina’s electoral maps slowly disappeared:

As the east-west divide grew harder to distinguish, a clear urban-rural divide has taken its place. I already mentioned above how Biden won most of the state’s most populous counties but the inverse held true as well. I pulled together a list of what I dub “Isolated Counties:” counties that have populations less than 50,000 residents and are not considered to be a part of a larger metropolitan area (according to the OMB). There are a total of 25 counties that fit this criteria and Donald Trump won every county in this subset that has a majority White voting base.

Forecasting the Future: What’s most surprising is that the state’s “Urban Crescent” is not immediately identifiable among counties won by Joe Biden. Known nationally as the “Piedmont Urban Crescent,” the region consists of ten counties and is home to seven of North Carolina’s ten largest cities. The development pattern of the region dates back to the North Carolina Railroad, built in the 1850s. Today the railroad operates as a vital freight artery, linking four of the state’s five largest cities and supporting much of the state’s recent economic growth. Assuming current trends continue, as these counties urbanize expect them to support Democratic candidates more forcefully. While Republicans are still gaining ground in the rural southeast, a region of the state that’s been progressively losing Democratic support for decades, it’s unlikely Republican gains here will be able to offset Democratic gains in more populous areas.